Refining the Question of Why

How Asking "Why?" Falls Short for Coaches

I try to write about concrete and actionable topics that coaches can implement on the field that very day. What’s more challenging though, is shifting the paradigms we use to coach. While this seems ethereal and New Age-y, thinking about how we think can significantly alter our real-world behaviors.

Over the past few years, one of the biggest questions that gets brought up at coaching courses and masters programs is “Why?” Why did you freeze the exercise here? Why did you say it like that? Why do you want this player to move here? Geez, why do you even coach? The phrase “find your why” seems to have been parroted around without a close examination of what it’s actually trying to achieve.

Truthfully I’ve grown to despise that question. It seems to have been fetishized and weaponized as if it’s a silver bullet that will solve every problem and grant enlightenment.

However... I begrudgingly admit that it is a good question. It’s a question that needs to be asked if we want to consistently improve and build upon best practices. But I do think that a blind adherence to asking Why will lead people to miss a fundamental aspect of coaching leadership.

To better understand the purpose of asking Why, it’s worth examining where the question came from.

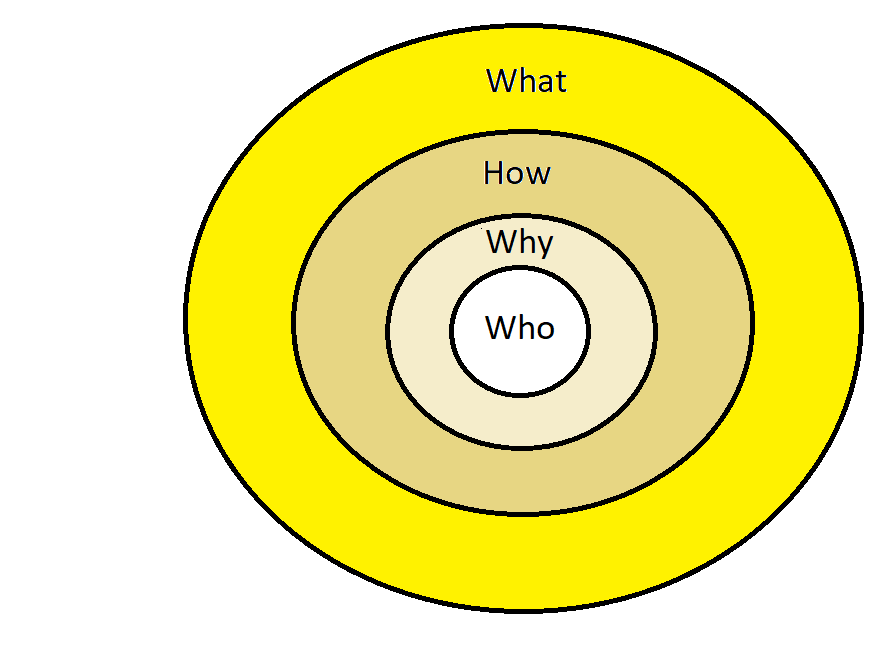

This will be an abbreviated history as I’m sure most of you are already familiar with Simon Sinek. He is the man who came up with what is known as the Golden Circle. The Golden Circle is best communicated through a diagram:

Sinek’s idea was simple: Too many people start from the outer edge of the circle. They focus on What they are going to do. These are the people who say “I’m going to make and sell cars.”

The next level of people who are moderately more successful are the ones who understand What they are going to do, and also figure out How they are going to do it. They say “I’m going to make and sell cars by creating the world’s first fully automated manufacturing process.”

Finally, the most successful people are the ones who start from the very center of the circle. The ones who understand Why they are doing what they do. They dramatically look to the skies and say “I’m going to create a fully automated manufacturing process to make and sell cars because we want to make the world happier by bringing people closer together.

Applying it to Coaching

While I agree with the sentiments behind this model I also find it deficient, especially in the context of coaching. The Golden Circle is primarily centered on communication rather than examining actions. There is a difference between asking “Why will these players listen to you?” versus “Why did you choose to run this exercise?” The first question is what Sinek would ask, the second is what a USSF coach educator would ask, but both are missing out on one fundamental aspect.

Nothing exists in isolation – as our world changes, we change as well. The Whys we choose need to be able to adapt and grow but they must be tethered to something deeper. Without a consistent undercurrent our Whys can shoot off in different directions. We become subject to sharp changes in our behaviors and goals as our motivations zig-zag back and forth. The athletes we lead will suffer psychological whiplash trying to keep up with our ever-changing impulses until they eventually play somewhere else or leave the game entirely.

So what I posit is that there is actually a fourth circle in play here: Who.

Knowing Who you are is crucial to the development process. And it’s worth noting that there are two diverging ways to think about this.

The first way can be described as personality-driven. We can use adjectives to describe ourselves (or at least our idealized future selves) such as brave, confident, diligent, etc. Certainly this is helpful in leveraging and developing strengths, particularly when they’re held in the context of a growth mindset. In those cases the language would then manifest itself as “I am becoming braver” or “Here is a moment I can choose to be brave,” or conversely, “I am not brave yet.” (although it’s worth nothing that there are problematic limitations within this which I will save for another time)

However, the second way of thinking about Who we are may be more important, especially for new coaches. This is Who you are in terms of the skills you possess, the strengths you have, and the environments you thrive in.

Every coach has different strengths that must be used to their advantage. Former players may lead best through modeling and demonstrations. Tactical aficionados may lead best by showing and teaching players how to play the game. Charismatic individuals may lead best by building tight networks of relationships throughout the team. In short, What, How and Why you do things is determined by Who you are.

Systemizing Strengths

Whatever your strength is, I suggest you find a way to systemize it. Create a clear method that ensures you can do what you do best while simultaneously refining your use of it. Here’s an example of how it may work:

Let’s assume your strength comes from being a good player thus your coaching strengths are modeling and demonstrating skills. You now must develop a method that capitalizes on it. Your method may be to choose one skill and focus on 3 different components within it. At training, you ask players to stand shoulder-to-shoulder as you demonstrate the skill five different times and highlight the three areas of focus. You then have them get in partners and practice with each other while you walk around and make comments.* This is something you do at every training session so players can anticipate and know the routine.

This method of teaching skills will change based on your preferences and best coaching practices. Maybe instead of players standing shoulder-to-shoulder you want each player to have their own ball and slowly re-enact the skill as you teach it. Maybe you don’t prefer partner-work but instead small groups. These are all things you can tweak and adjust until you find a method that you are comfortable with, and then you perfect it.

Of course these systems will always need adjusting. An easy example is shooting; players need a goal to practice shooting, it’s not something they can do in partners, thus the system I mentioned above would need to change in that context. It’s important that whatever method you use matches the appropriate context while still abiding by best coaching principles (which will be another article in the future).

Here’s another example: Your strength resides in managing social groups. Before every practice you greet each player individually. During the first team huddle you ask a general question to the team and players answer voluntarily. During the second team huddle you ask a question which they must discuss in groups before presenting their answers to everyone. Before the scrimmage you give them specific tactical objectives which they must decide on as a team how to achieve. At the end of practice you review the topic and reflect as a group on their interactions.

Again, this is a method that can used be systematically and refined over time. There will be parts you like and parts that don’t work. But it’s not about getting things right – it’s about methodically learning about and developing your strengths, while understanding the principles that operate underneath them.

Finding Strengths Elsewhere

As stated in the final quote of my 5 Books for New Coaches article, it’s important to look outside of our narrow field for inspiration and information. The same is true for understanding Who we are as coaches. It’s possible that our strengths that seem totally unrelated to coaching may actually be incredibly helpful once our paradigms shift.

For example: when I was a young coach I was once asked what my strengths were. I quietly sat there for a minute or two while contemplating my answer. My mind remained blank until I finally blurted out “I’m good at writing emails.” Now on the surface this has very little to do with with the actual act of coaching. But with the benefit of hindsight, I realized what I actually meant was “I’m good at writing,” and today I use that skill all the time. Before every training session I carve out time to write lesson plans containing small speeches and coaching points.

Here’s another example: I once coached a group of U9 players with another coach. Young players are notoriously difficult to manage, but she seemed to have complete and total control over them. It was only after a few training sessions that I realized how she did it. She would alternate between speaking softly and speaking loudly, and through her tone of voice she could convey whether it was time to play or time to pay attention. When I asked her about it she told me that she grew up singing in a choir and still sang regularly. She had turned her total control of volume, pitch, tone, and intonation into a sharp coaching tool.

As coaches we have the opportunity to shape learning environments into what suits us best. While leveraging strengths is a skill onto itself, I do believe the greatest benefit it creates is the goodwill that it engenders. Perfecting what we do well gives us the space to improve what we don’t do well. Every youth coach needs to be able to teach technical skills, guide tactical prowess, build healthy relationships, and more. But mastery requires a layering of skills. If we only focus on strengthening weaknesses then the collateral damage will result in players leaving. Instead we must strike a balance between perfecting what we do best and developing areas that need to improve. Finding this symmetry may be difficult, but it is crucial to discovering – and creating – Who you are.

*We can talk later about isolated practice vs pressured practice.